Prince in the cloud - splat!

We use DocRaptor to generate PDFs for our customers; over 60,000 on-demand custom reports generated using their data per month. At least, we used to.

DocRaptor is a fantastic service, but generating that volume of documents costs us a pretty penny. At the time of writing, 40,000 PDFs a month is the highest tier they offer before you get into ‘contact us’ territory, and we were frequently going over that limit.

For those unfamiliar, DocRaptor is a service that offers you an API to send HTML, CSS and javascript to. It generates a PDF and streams it back to you as a binary response. At the core of this process is a commercial product called PrinceXML.

We got in contact with YesLogic, the folks behind PrinceXML, and while not cheap, a yearly licence for prince was significantly more economical than our DocRaptor plan. Being a frugal little startup, this presented an opportunity to save some money.

However, we had to be careful. We’re talking about actually re-inventing the wheel here. There was a very real risk that maintaining our own PDFing service could cost us more than any money we saved on DocRaptor.

For us, the advantages outweighed the risk: we could use a newer version of prince that supported features like CSS grid. We could potentially save our PDFs directly to S3, instead of transferring them over the internet multiple times, and we could make use other features of prince, like PDF merging.

Our Requirements

Like any project, you should approach with some goals in mind. Why are you doing it, and what’s your measure of success? Here’s what we wanted coming out of this:

Same interface. To replicate the convenience of DocRaptor, and make integration as simple as possible, we wanted to set up our own API, with the same interface. Our solution should be a drop-in replacement.

Reliability. DocRaptor generally ‘just works’; they’ve had a team refining and fixing bugs in their product for years. Creating our own service means potentially making the same mistakes and having to fix the same bugs they’ve already dealt with. If it breaks, it costs us developer time to get it working again, negating any cost savings.

Speed. Docraptor is not slow, and our solution shouldn’t be any slower. We clocked DocRaptor at about ~3-4 seconds for a simple document, end to end.

Splat is Born

What does splat stand for, Agent Ward? Serverless Prince Lambda Any Time. And what does that mean to you? It means someone really wanted our initials to spell out “splat”.

AWS Lambda seemed like a neat, cheap way to run small, independent jobs on demand, offering automatic scaling. It wouldn’t matter if we requested 1 document per minute, or 10,000.

Firstly, AWS lambdas in a nutshell. Lambdas are AWS’s offering of Function as a Service (FAAS). Basically, you write code, zip it up, store it on AWS, and when something ‘invokes’ your lambda function, it runs the code from your defined entry point and returns some data. Pretty simple, but the whole process is handled automatically by AWS. You don’t need to worry about scaling, if your lambda needs to be invoked 100 times at once, AWS just magically provisions 100 servers and runs your function on them. There’s a small time cost in provisioning a server for your code to run on (which is an area of heavy focus for any FAAS offering), but lambdas hang around for a little while before they get removed, so you generally don’t incur the startup cost very often.

Running Binaries on AWS Lambda

We decided to write our lambda in python because we love python. So how do we run a binary like PrinceXML from a python lambda? Is it even possible to run subprocesses in a lambda environment? The answer is yes!

A naive approach would be to have the lambda download PrinceXML, extract it, set it up and run it every time. It’s fairly obvious that this is a slow and error-prone process. What if prince’s download servers are slow? Or down?

The better approach is to pre-download and pre-setup your binary and any libraries it needs. Then just include that in your zip bundle you send to lambda. We automated this process in splat’s installation script; check out splat, specifically in tasks.py to see it in action.

Invoking your binary from python is fairly straightforward. Just pass your command as a list to subprocess.check_output and catch any exceptions. Here’s an example from splat: command = [ ‘./prince/lib/prince/bin/prince’, input_filepath, ‘-o’, output_filepath, ‘–structured-log=buffered’, ‘–verbose’, ] if javascript: command.append(‘–javascript’) # Run command and capture output try: output = subprocess.check_output(command, stderr=subprocess.STDOUT) except subprocess.CalledProcessError as e: output = e.output

Exposing a Lambda as an API

The best way to expose your lambda as an API service is using AWS API Gateway. Setting it up is a little difficult though. AWS documentation on the topic is pretty sparse, and it gets more complicated if you want to return a mix of binary data and json responses.

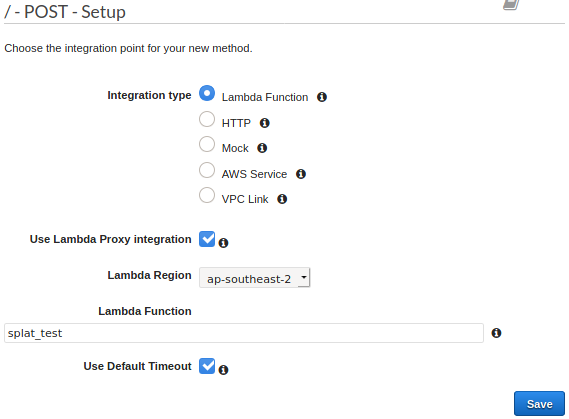

There’s two ways to use API Gateway to run your lambda functions, provided by the ‘Use Lambda Proxy integration’ checkbox on the Integration Request section of your API Gateway method. Depending on which you choose, your lambda needs to accept and return different data.

In our case, we want to enable proxy integration, which kind of dumbs down the API Gateway, and it simply passes the request through to your lambda, instead of applying transformations and mappings to the request. This means we need to do more work inside our lambda to extract the information we want, and likewise, when you return data from your lambda, you need to specify more information, including the status code and headers.

Your lambda function takes two parameters, event and context. Since we’re using the proxy integration, event contains everything about the API request, including HTTP request headers and the body. We simply extract the body, load it with the JSON library, and access whatever information we need from it. After the lambda function has done whatever it needs to do, we need to return a response. This may be as simple as just responding with ‘OK’, but in our case, we needed to stream back binary data if the PDF generation was successful, and return a meaningful error in JSON if something went wrong.

Here’s a simplified example of how splat works:

import base64

import json

# Entrypoint for AWS

def lambda_handler(event, context):

red_square = 'R0lGODdhFAAUAIABAP8AAP///ywAAAAAFAAUAAACEYSPqcvtD6OctNqLs968+68VADs='

body = json.loads(event.get('body') or '{}')

if body.get('binary'):

return {

'statusCode': 200,

'headers': {

'Content-Type': 'image/gif',

},

'body': red_square,

'isBase64Encoded': True,

}

else:

return {

'statusCode': 200,

'headers': {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

},

'body': json.dumps('Hello world!'),

'isBase64Encoded': False,

}

Fairly simple. If we pass {"binary": true} as body text to our API, we expect to get a red square streamed back to us as binary data. If we don’t pass anything, or pass false we expect a json response. In splat, we send HTML, generate the PDF, encode the resulting file and send that back with Content-Type: application/pdf, and if something goes wrong, we return the details of the error in a json response, with an appropriate statusCode.

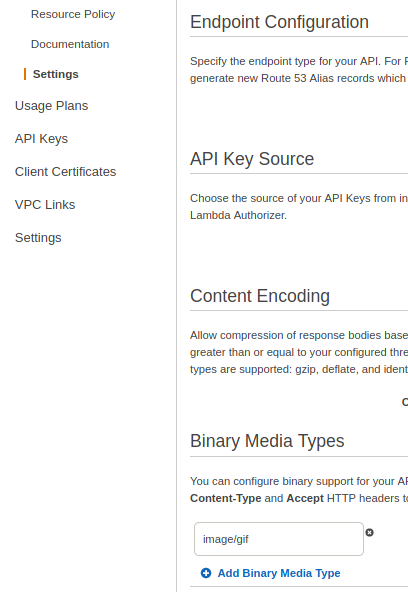

The important part here is the structure of the response, and the isBase64Encoded option. In the API Gateway settings we also need to specify which content types are treated as binary. I can’t think of a good reason why you need to specify both this setting and isBase64Encoded in the response, but it is required.

Full example

This is how splat sets up the API Gateway, but shown using the AWS console, in case anyone finds it useful for setting up their own microservices in the same fashion.

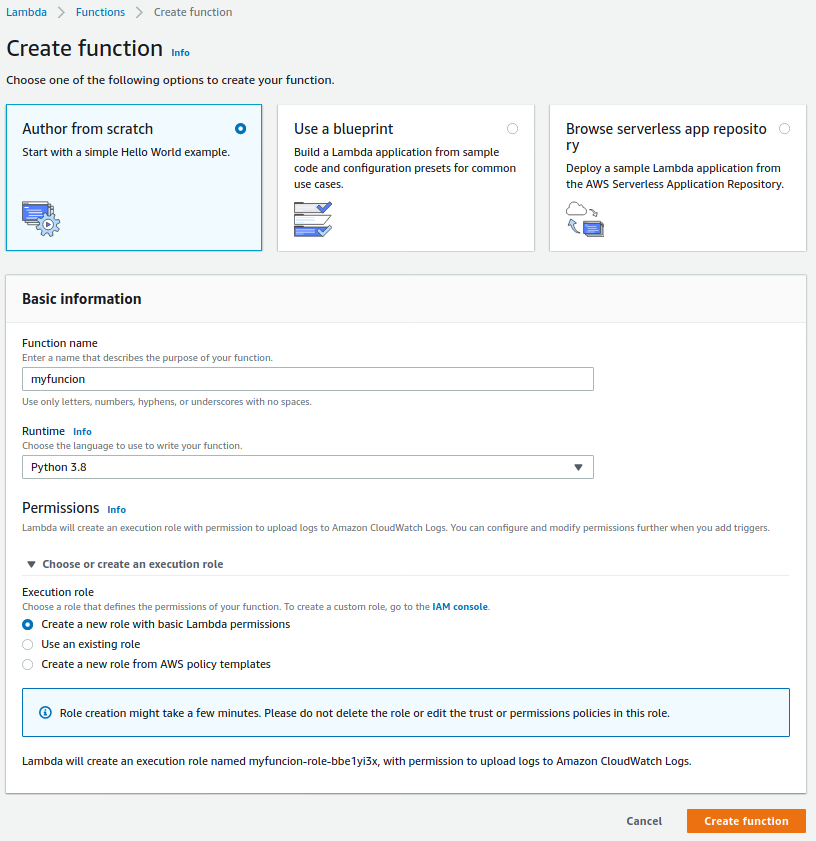

First, we make a role for our lambda to use, and we give it the default lambda policy, and a basic execution policy. This is equivalent to making a role when you create your lambda from the AWS console.

We create our lambda function, uploading our lambda code as a zip file, or copying it manually into the editor.

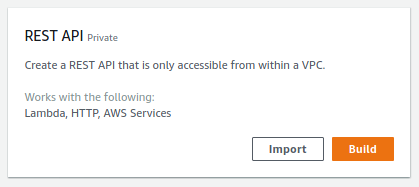

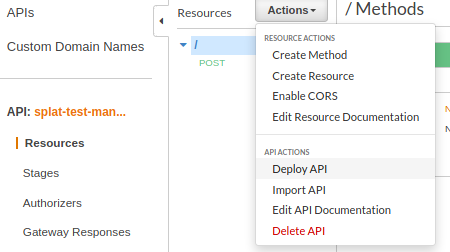

We create an API Gateway REST API.

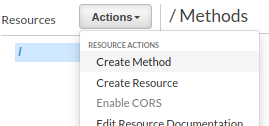

On the API we create a POST method on the root (/)

Select our lambda as the integration for our new method. Ensure you check “use lambda proxy integration”

Next, we need to tell our API to treat certain content types as binary. In the API settings, for our example, enter image/gif.

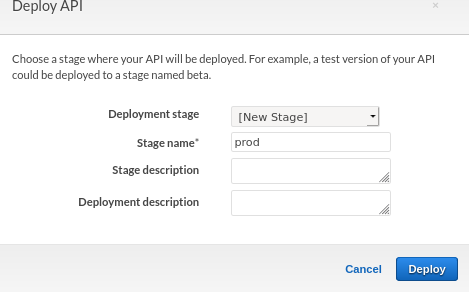

Next, we deploy the API, creating a stage.

Call it prod, or whatever else you like.

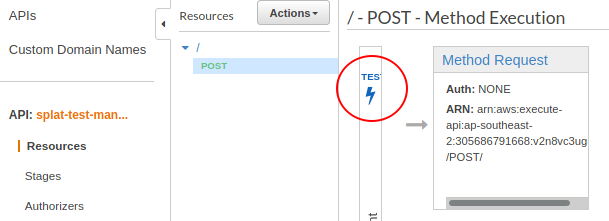

If all goes well, you should have a URL you can test out. First, let’s try amazon’s built-in API test. Browse back to the post method, and click ‘test’.

If you click test, with no text in the body, you should get back "Hello world!" with content type application/json.

If you enter {"binary": true} for the body, you should get base64 returned with content type image/gif.

If you access the endpoint URL provided when you deployed your application, and send {"binary": true} as the body, and importantly, send an Accept: image/gif header, you should be streamed back binary data.

Like so:

curl https://whatever.execute-api.your-region.amazonaws.com/prod -H 'Accept: image/gif' --data '{"binary": true}' > redsquare.gif

Even with the accept header set to a binary format, our API will return a json response just fine, in this case if you omit the mode body, or in a real world case, an error occurs.

Final thoughts

- Splat seems to be an order of magnitude faster than DocRaptor.

- Reinventing the wheel is not a good idea… unless it saves you a bunch of money.

- Use lambda proxy integration. The rest of API Gateway is pointlessly complex, and this bypasses it.

- Make sure your lambda returns a dictionary response with all the relevant information, including status code.

- Make sure you set up binary media types in the API settings.

- Return base64 encoded data from your lambda, setting isBase64Encoded to true.

- Check the response code and content-type header of response and use the data accordingly.

- Don’t forget to redeploy your API after changes, or you may be confused why things didn’t work.

- Lambda is really, REALLY cheap. 100,000 PDF’s, taking 400ms and 512mb memory each only costs us 35 CENTS.

If you’re interested in checking out our solution, it’s available on github here. If you intend to use it, make sure you do so within prince’s licensing agreement.